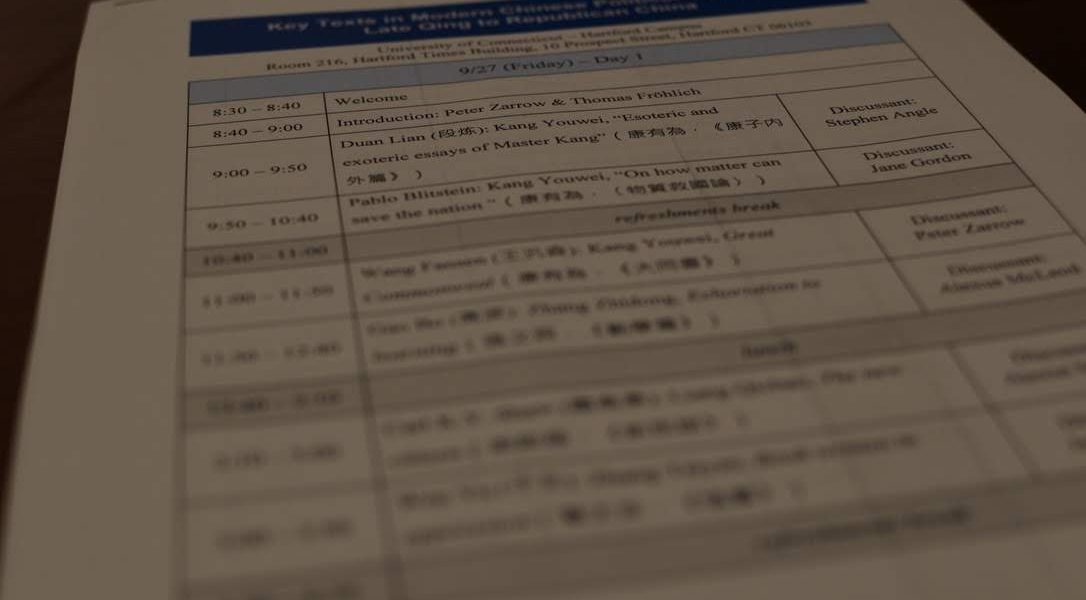

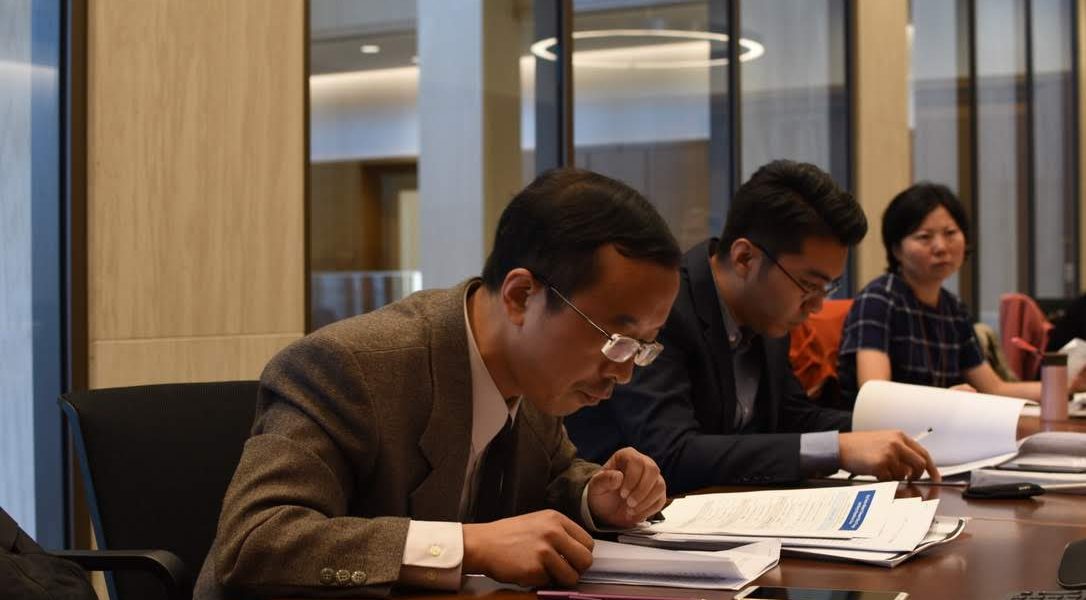

Fifteen scholars from China, Taiwan, and Europe, as well as the US, met on September 27 and 28, 2019 to discuss selected key texts written by Chinese intellectuals and political activists from the late Qing period (1890s) through the Republican period (1912-1949). The conference was held at UConn-Hartford.

The texts ranged from well-known works by Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao, and Mao Zedong to lesser-known writings of Yang Du and Ding Shan. The conference’s discussions were held in English and Chinese. Duan Lian, Pablo Blitstein, Wang Fansen, Gao Bo, Carl K.Y. Shaw, Wen Yu, Mara Yue Du, Axel Schneider, Gu Hongliang, Thomas Fröhlich, Li Yongjin, Shellen Wu, and Peter Zarrow gave papers, while discussants were Stephen Angle, Alexus McLeod, and Fred Lee.

The goals of the conference were to highlight new scholarship on the rich political theorizing of the period, and to help establish modern Chinese political thought as a field not only important in its own right but of interest to non-Sinophone scholars working on political theory, comparative politics, and global intellectual history. We collectively hope to continue to pursue these goals in the future. In terms of making modern Chinese political thought more transparent outside this sub-field, we will work on providing complete translations of key texts and, separately, introductions to them. These introductions will provide basic information on the text’s author, its context, its contents and significance, and its reception and influence. Both translations of complete texts and introductions to them should be of use to scholars and students. At the moment, we lack these scholarly tools—most of the translations we have are highly abridged or limited to a small number of political leaders (Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong). And the monographic literature speaks mostly to specialists.

Papers and discussion at the UConn conference centered around such themes as materiality, utopianism, and temporality, as well as more familiar topics such as secularization, legitimacy, and rights and liberty. We did not come up with a clear definition of what constitutes a “key text” and do not want to establish a canon, but rather we hope to keep open what texts are of historical and contemporary interest. Loosely speaking, we can put key texts into one of two categories: historical importance as defined by the text’s reception and influence (at the time it was disseminated or later); and intrinsic interest as defined by the text’s originality and argumentation. This conference made no attempt to claim the texts discussed could possibly represent the spectrum of political thought in twentieth-century China, but it did include texts that represented a variety of opinion—articles and books by Kang Youwei, Zhang Zhidong, Liang Qichao, Zhang Taiyan, Yang Du, Chen Duxiu, Liang Shuming, Ding Shan, Luo Longji, and Mao Zedong.

Much Chinese writing of the period of course constituted adoption, adaptation, and reflections on ideas that originated in Euro-America and Japan (or via Japan). At the same time, the influence of Confucian and Buddhist ideas on particular texts was profound. In approaching key texts, it is necessary to keep in mind various authors’ particular and original interpretations of the of the questions they were asking. The afterlife of texts is also worth considering; for example, China today has seen a revival of certain texts written a hundred years ago such as writings of Kang Youwei, which interest New Confucians, and writings of Zhang Taiyan (Binglin), which interest New Left thinkers.

In addition to opening up the question of the exact bases of modern Chinese political thought by focusing on key texts, this conference also raised the question of what counts as “political thought” in the first place. Discussions turned to the problem of the hegemony of Western political methodologies and problems, the need to encourage more comparative work, and the advantages of interdisciplinary scholarship, especially among historians, political theorists, and philosophers.

Sponsors of the conference were the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation; and UConn’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Dean’s Office, Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, Humanities Institute, Department of History, Office of Global Affairs, and Department of Philosophy. Photo Credit: Jason Chang.