On February 4th, Jane C. Hu published an article titled “The Panic Over Chinese People Doesn’t Come From Coronavirus” in Slate. The article includes thoughts from Professor Jason Oliver Chang on the history behind the racialized thinking of Asians as disease carriers. Professor Chang is an Associate Professor of History and Asian American Studies, and Director of UConn’s Asian and Asian American Institute. To read the article, click here.

On February 4th, Jane C. Hu published an article titled “The Panic Over Chinese People Doesn’t Come From Coronavirus” in Slate. The article includes thoughts from Professor Jason Oliver Chang on the history behind the racialized thinking of Asians as disease carriers. Professor Chang is an Associate Professor of History and Asian American Studies, and Director of UConn’s Asian and Asian American Institute. To read the article, click here.

Inside Higher Ed Features Contingent Magazine’s First Year

On January 27th, Inside Higher Ed helped recognize the first year of Contingent Magazine, an online history publication written and edited by trained historians for the public, by publishing an article titled “1 Year Down“. The feature highlights the inspiration behind the creation of Contingent Magazine, the experience of its first year, and where the magazine is heading. As described by Inside Higher Ed, “Contingent Magazine had a lot of doubters when it debuted 12 months ago. But it’s still going strong and earning a reputation as a place where historians can engage the public with the ideas that have always interested them.”

The detailed feature includes interviews with UConn History Ph.D. Erin Bartram and Ph.D. Candidate Marc Reyes. Bartram serves as Contingent‘s co-founder and Reyes an editor. According to Bartram, an “advocate for the field she loves,” but not the larger structural problems, she asked herself in 2018: “‘What can I do? I can start a magazine with my friends and edit and pay scholars for their work… I don’t necessarily think it will change things structurally, but it matters to the people who get $250 per piece.”

According to Reyes, he is most “proud of the types and topics of the articles we have run so far, including features, photo essays, and a cartoon. Most recently, in parallel with the 2019 release Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, Contingent released Star Wars-inspired features, “If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Batuu” and “Sacred Objects,” which investigates how the medieval era inspired the Star Wars universe. In December, during the release of the Star Wars features, the website received 23,000 views. Funded entirely by its loyal readers through small donations, Contingent continually has provided enticing, intellectually provocative features and “postcards” from conferences.

To read more about Contingent Magazine and its successful first year, please click here.

Prof. McKenzie Presents Talk for World Fish Migration Day

Matthew McKenzie, Professor of History at UConn-Avery Point, recently presented as a speaker in the World Fish Migration Day Lecture Series (sponsored by The Wildlands Trust) in Pembroke, Massachusetts. Professor McKenzie’s talk was titled “Old Friends in a New World: Early English Settlers’ Annual Calendars of New England Fish Arrivals.” Although World Fish Migration Day is not until May 16th, there is no question that Professor McKenzie’s lecture and research helped kick off the celebrations!

Matthew McKenzie, Professor of History at UConn-Avery Point, recently presented as a speaker in the World Fish Migration Day Lecture Series (sponsored by The Wildlands Trust) in Pembroke, Massachusetts. Professor McKenzie’s talk was titled “Old Friends in a New World: Early English Settlers’ Annual Calendars of New England Fish Arrivals.” Although World Fish Migration Day is not until May 16th, there is no question that Professor McKenzie’s lecture and research helped kick off the celebrations!

A video recording of his lecture can be found here.

Prof. Manisha Sinha Interviewed by Democracy Now

On January 22, Draper Chair and Professor Manisha Sinha was interviewed by Democracy Now! to discuss the similarities between President Trump’s impeachment trial in the Senate and historical similarities to President Andrew Johnson. An 18 minute recording of the interview can be found here with the title of “‘Andrew Johnson Was A Lot Like Trump’: Echoes of 1868 in Trump’s Impeachment Trial”.

On January 22, Draper Chair and Professor Manisha Sinha was interviewed by Democracy Now! to discuss the similarities between President Trump’s impeachment trial in the Senate and historical similarities to President Andrew Johnson. An 18 minute recording of the interview can be found here with the title of “‘Andrew Johnson Was A Lot Like Trump’: Echoes of 1868 in Trump’s Impeachment Trial”.

Contingent Magazine Spotlight of UConn Alum, Nick Hurley

Contingent Magazine recently featured Nick Hurley, UConn History B.A. ’13 and M.A. ’15, in his fascinating role as Curator at the New England Air Museum. As part of the magazine’s series on how trained historians “do history,” Nick shared what a “typical day” is like for him (hint: it varies greatly and can include inspecting donated aircraft) and shared how his family’s German origins sparked his interest in history.

Contingent Magazine recently featured Nick Hurley, UConn History B.A. ’13 and M.A. ’15, in his fascinating role as Curator at the New England Air Museum. As part of the magazine’s series on how trained historians “do history,” Nick shared what a “typical day” is like for him (hint: it varies greatly and can include inspecting donated aircraft) and shared how his family’s German origins sparked his interest in history.

Nick also shares how his historical training in Wood Hall and at the UConn Archives & Special Collections helped prepare him for this role. He says: “I knew very little about aircraft and aviation history before starting this job. What I did have, however, was a firm grasp on the fundamentals of historical research thanks to my work in graduate school, as well as an understanding of collections management, access, and care thanks to my time with UConn Archives & Special Collections. Put simply, I knew how to read, write, and speak effectively, and I could draw on my own experiences from both sides of the reference desk to help figure out what visitors (to both our research library and the museum itself) expected and wanted to see.”

To read the full interview, click here.

Mahoney and Horrocks’ American Girls Podcast Featured on WNPR

On December 25, 2019, Connecticut Public Radio (WNPR) featured an interview with American Girls Podcast hosts (and UConn PhDs) Mary Mahoney and Allison Horrocks. The feature, titled “How The American Girl Dolls Inspired a Cult Podcast,” shares the history behind the podcast, the creation of the American Girl empire, and the large impact that the podcast is having on its loyal listeners. To read, or listen, to the feature, click here.

4 History Students Named to 2020 University Scholars

Four of the twenty-three students named to UConn’s 2020 University Scholars are History majors or working closely with History faculty. Congratulations are in order for Jenifer Gaitan, Shankara Narayanan, Alexander Mika, and Shanelle Jones! Wood Hall would like to thank Professors Sara Silverstein, Joel Blatt, Frank Costigliola, and Alexis Dudden (among others) for their dedication to assisting and mentoring these students. See below for details of each student:

Jenifer Gaitan

Major: History

Project Title: Voces: First-Generation Latinx Students Discuss Their Support Networks

Committee: Laura Bunyan, Sociology (Chair); Ingrid Semaan, Sociology and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies; and Joel Blatt, History

Shanelle Jones

Major: Political Science and Human Rights

Project Title: Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the U.S.

Committee: Charles Venator-Santiago, Political Science (Chair); Virginia Hettinger, Political Science; and Sara Silverstein, History and Human Rights

Alexander Mika

Major: English

Project Title: An Exploration of Nationalism and Jingoism through Drama

Committee: Ellen Litman, English (Chair); Evelyn Tribble, English; and Frank Costigliola, History

Shankara Narayanan

Major: Political Science and History

Project Title: The Logic of Rising-Power Strategy: China, Imperial Japan, Imperial Germany, and the United States

Committee: Alexis Dudden, History; Alexander Anievas, Political Science; and Frank Costigliola, History

Ph.D. Student Phil Goduti Named CT Outstanding Teacher of the Year

Ph.D. student Philip Goduti has been named the Connecticut Outstanding Teacher of American History for 2020 by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The award is given to a teacher that demonstrates excellence in: readily sharing an incisive knowledge of American History, being committed to their students, fostering a spirit of patriotism and loyal support of our country, relating history to modern life and events, and requiring high academic standards at all times from their students.

Ph.D. student Philip Goduti has been named the Connecticut Outstanding Teacher of American History for 2020 by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The award is given to a teacher that demonstrates excellence in: readily sharing an incisive knowledge of American History, being committed to their students, fostering a spirit of patriotism and loyal support of our country, relating history to modern life and events, and requiring high academic standards at all times from their students.

Phil has gone beyond the call of teaching duty to demonstrate these attributes in the classroom and inspire his students at Somers High School. Phil will be competing for the national DAR award this spring. Good luck!

PhD Candidate Lauren Stauffer Presents at NATO Conference

On December 6th, Ph.D. candidate Lauren Stauffer presented at a one-day conference titled “NATO: Past and Present“. The conference was held at the Sir Michael Howard Centre of King’s College London, and co-sponsored by Cardiff University and the Wilson Center. The event “brought together leading scholars of NATO from Europe, Canada, and the United States to evaluate the balance sheet of the alliance’s 70 year-history.” Stauffer’s conference paper, titled “NATO and the Iran-Iraq War: How “Out-of-Area” Concerns Paved the Way to a Post-Cold War Future,” featured research from her dissertation that draws on recently de-classified NATO and government documents.

On December 6th, Ph.D. candidate Lauren Stauffer presented at a one-day conference titled “NATO: Past and Present“. The conference was held at the Sir Michael Howard Centre of King’s College London, and co-sponsored by Cardiff University and the Wilson Center. The event “brought together leading scholars of NATO from Europe, Canada, and the United States to evaluate the balance sheet of the alliance’s 70 year-history.” Stauffer’s conference paper, titled “NATO and the Iran-Iraq War: How “Out-of-Area” Concerns Paved the Way to a Post-Cold War Future,” featured research from her dissertation that draws on recently de-classified NATO and government documents.

“Key Texts” In Modern Chinese Political Thought Conference

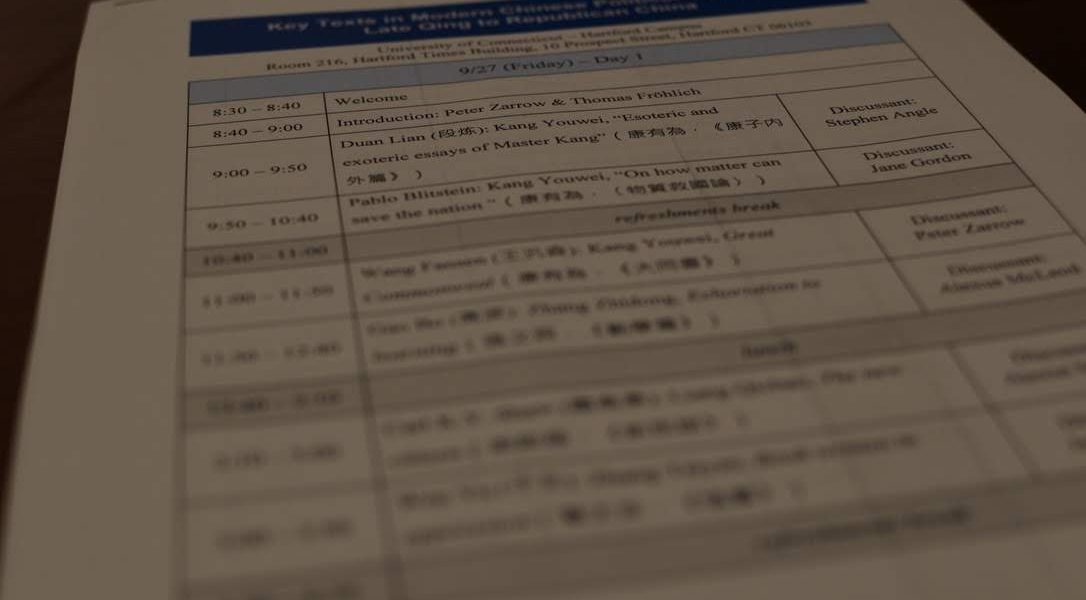

Fifteen scholars from China, Taiwan, and Europe, as well as the US, met on September 27 and 28, 2019 to discuss selected key texts written by Chinese intellectuals and political activists from the late Qing period (1890s) through the Republican period (1912-1949). The conference was held at UConn-Hartford.

The texts ranged from well-known works by Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao, and Mao Zedong to lesser-known writings of Yang Du and Ding Shan. The conference’s discussions were held in English and Chinese. Duan Lian, Pablo Blitstein, Wang Fansen, Gao Bo, Carl K.Y. Shaw, Wen Yu, Mara Yue Du, Axel Schneider, Gu Hongliang, Thomas Fröhlich, Li Yongjin, Shellen Wu, and Peter Zarrow gave papers, while discussants were Stephen Angle, Alexus McLeod, and Fred Lee.

The goals of the conference were to highlight new scholarship on the rich political theorizing of the period, and to help establish modern Chinese political thought as a field not only important in its own right but of interest to non-Sinophone scholars working on political theory, comparative politics, and global intellectual history. We collectively hope to continue to pursue these goals in the future. In terms of making modern Chinese political thought more transparent outside this sub-field, we will work on providing complete translations of key texts and, separately, introductions to them. These introductions will provide basic information on the text’s author, its context, its contents and significance, and its reception and influence. Both translations of complete texts and introductions to them should be of use to scholars and students. At the moment, we lack these scholarly tools—most of the translations we have are highly abridged or limited to a small number of political leaders (Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong). And the monographic literature speaks mostly to specialists.

Papers and discussion at the UConn conference centered around such themes as materiality, utopianism, and temporality, as well as more familiar topics such as secularization, legitimacy, and rights and liberty. We did not come up with a clear definition of what constitutes a “key text” and do not want to establish a canon, but rather we hope to keep open what texts are of historical and contemporary interest. Loosely speaking, we can put key texts into one of two categories: historical importance as defined by the text’s reception and influence (at the time it was disseminated or later); and intrinsic interest as defined by the text’s originality and argumentation. This conference made no attempt to claim the texts discussed could possibly represent the spectrum of political thought in twentieth-century China, but it did include texts that represented a variety of opinion—articles and books by Kang Youwei, Zhang Zhidong, Liang Qichao, Zhang Taiyan, Yang Du, Chen Duxiu, Liang Shuming, Ding Shan, Luo Longji, and Mao Zedong.

Much Chinese writing of the period of course constituted adoption, adaptation, and reflections on ideas that originated in Euro-America and Japan (or via Japan). At the same time, the influence of Confucian and Buddhist ideas on particular texts was profound. In approaching key texts, it is necessary to keep in mind various authors’ particular and original interpretations of the of the questions they were asking. The afterlife of texts is also worth considering; for example, China today has seen a revival of certain texts written a hundred years ago such as writings of Kang Youwei, which interest New Confucians, and writings of Zhang Taiyan (Binglin), which interest New Left thinkers.

In addition to opening up the question of the exact bases of modern Chinese political thought by focusing on key texts, this conference also raised the question of what counts as “political thought” in the first place. Discussions turned to the problem of the hegemony of Western political methodologies and problems, the need to encourage more comparative work, and the advantages of interdisciplinary scholarship, especially among historians, political theorists, and philosophers.

Sponsors of the conference were the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation; and UConn’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Dean’s Office, Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, Humanities Institute, Department of History, Office of Global Affairs, and Department of Philosophy. Photo Credit: Jason Chang.